Connecting to Wi-Fi networks that use a login webpage

When you’re connecting to a Wi-Fi network to access the internet you’ll be connecting to either an open network or a secured network. If a Wi-Fi network is an open network, you will be able to connect to it easily, but you may not be able to use it to access the internet. You’ll find this out when, after you have connected to the Wi-Fi network, you try to use your email client or your browser and neither of them work. If so, you are probably connected to an open Wi-Fi network that uses a login webpage.

If you have connected to an open Wi-Fi network that has a login webpage, when you try to open any webpage on your browser you should, instead, get the login webpage for the Wi-Fi network, so that you can provide the necessary details to connect to the internet.

Unfortunately, this process is notoriously unreliable, and you will almost certainly get a warning that there is no internet, and instructions to check cables and check connections and the like. The reason for this is a bit technical, but I’ll go through it briefly, and then give you the solution.

The URL (web address) for most webpages that you use start with ‘https…’; the ‘s’ on the end means that the webpage uses a secure internet protocol. A rule of that secure internet protocol is that the webpage can’t be replaced with another, different, webpage.

When you connect to an open Wi-Fi network that requires a login webpage the modem Wi-Fi router tries to replace the webpage that you are opening with its login webpage, but if the webpage you are opening uses the https protocol – and most webpages do – you browser will refuse to allow the replacement to occur, and will show an error.

The solution to this problem is to open a webpage that uses the older http protocol, which few webpages now use. If you don’t know of any webpages that use the http protocol you can use this one: neverssl.com, which has been created just to solve this problem, or you can use example.com or example.org, which are maintained by the Internet Assigned number Authority, and are easy to remember. When you open a webpage that uses the http protocol, the modem Wi-Fi Router will immediately replace it with its Wi-Fi network login webpage, allowing you to enter the necessary details to connect to the internet.

Limitations of Wi-Fi networks that use a login webpage

Commonly, with a connection to an open Wi-Fi network that has a login webpage, you access to the internet may be limited to a particular amount of connection time, or a particular quantity of downloaded data, after which your connection will stop. This sort of connection may also be intentionally slowed to limit your internet use to using static websites and checking your email.

A connection to an open Wi-Fi network may appear to be ‘free’; but, in fact it's not, and you must pay for it in some other way. Perhaps your access to the network is associated with your paid use of a business’s services, or you may have to pay for it with information about yourself, or you may have to actually pay for it with money.

Once you get the login webpage there are a few scenarios that you may encounter, with different terms, conditions, and configurations. These are the scenarios for connecting to an open Wi-Fi network that uses a login webpage that I have come across.

An open connection with a simple login webpage

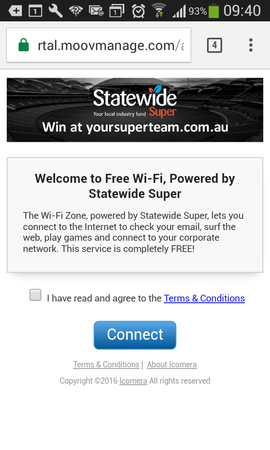

When the login webpage opens in your browser the process to connect is simple. This is the Login webpage for a public Wi-Fi network in Adelaide, South Australia:

To access the internet on this free Wi-Fi network you just have to accept the terms and conditions of the Wi-Fi network’s owner by selecting a tick box, and click on a button with connect on it. This one is an especially good deal for a public Wi-Fi network – free and unlimited – someone’s superannuation is paying for your internet!

An open connection with a login webpage that requires a password

When the login webpage opens in your browser it will have a field for you to enter password, like this login webpage for a Wi-Fi network in a government medical centre (don’t ask) in Adelaide, South Australia:

To access the internet, you’ll need to get the password from the business’s staff, and you may need to pay for it.

A open connection with a login webpage that requires personal information

This type of connection is 'free' because you must pay for it by handing over personal information before you can access the internet.

The information that is collected may be basic travel information such as your home town, your means of transport to get to the location where the Wi-Fi is being provided, why you have come to the area, and how long you will be staying there, all of which is collected for a survey – that’s all quite innocuous.

You may also be asked for basic demographic information such as age, nationality, gender, income band, and personal preferences in different fields – that’s a bit more intrusive, but still pretty innocuous.

More intrusively, you may be asked for contact details such as your email address, your phone number, and even your postal address. Consider carefully whether the free internet access is worth the consequences of handing over this information – you could be setting yourself up for a life-time supply of spam email, nuisance phone calls, personally addressed junk mail, and even a robbery at home while you are away.

This is the login webpage for the free Wi-Fi network at Meadow Mews shopping centre in King’s Meadow, Tasmania:

They want my email address! Of course, you can easily put in fake information, although they may send you a confirmation email that you must respond to before they let you in. I’m usually happy to give a disposable email address that I’ve set up just for this purpose if the business seems reputable, but I never give my phone number or my residential address (partly because I don’t have a residential address.)

All this data entry is barely worthwhile if you also have mobile data and you're trying to save it for when you can't get a Wi-Fi connection; but if you’re only visiting a country for a very short stay, setting up mobile data will be a bit of mucking around too, and will cost you money.

Disclaimer

This commentary is based on my personal experiences and impressions -- it isn’t the result of an exhaustive study of Wi-Fi networks that have login pages and how to connect to them. My comments are based on the specific devices that I use, and the circumstances that I encounter as I use them. It may not apply to you, or your equipment or circumstances.

Over time, this commentary may become out of date, and, while I’ll correct anything I know is wrong, I’m not going to be excessively conscientious about it. So, treat this as a great place to start, but do your own research before committing to anything!